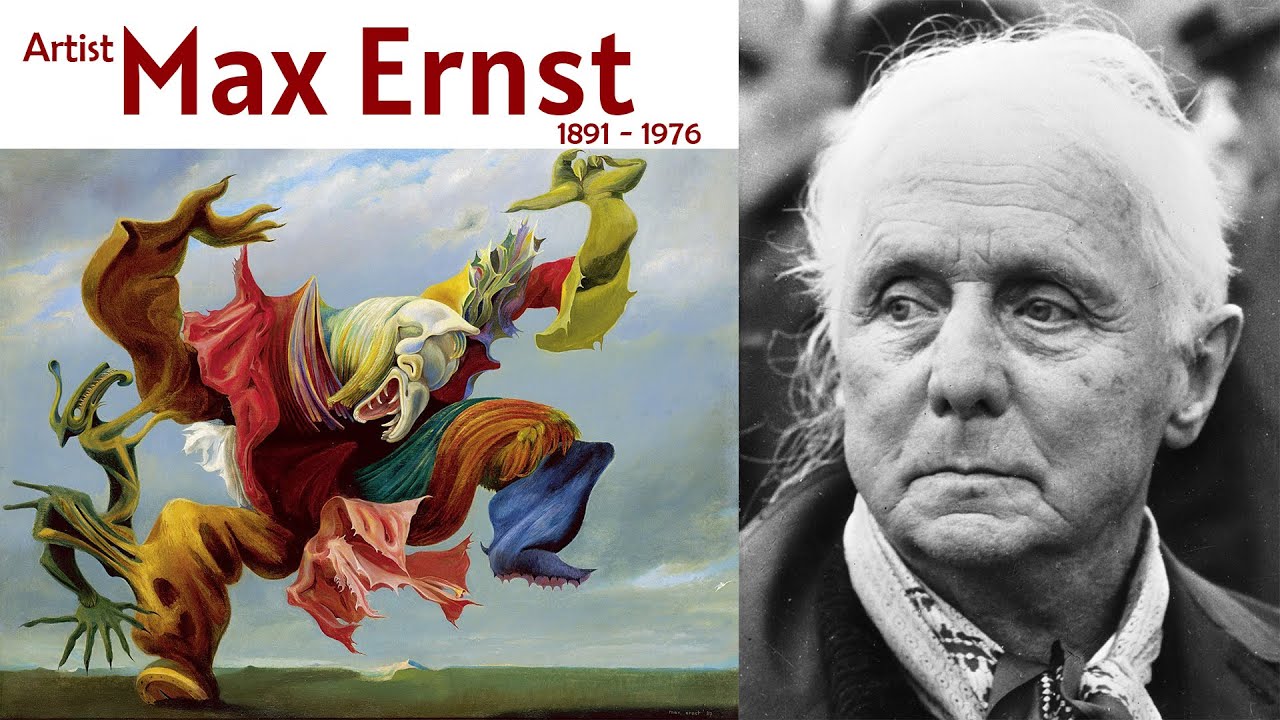

Robert Draws – Max Ernst was not just a painter. He was a force that shattered the conventional structure of art and thought. Emerging from the turbulence of post-war Europe, he helped launch the Dada movement before diving deep into the shadows of Surrealism. His work is filled with arcane symbols, dreamlike figures, and eerie biological forms that seem torn from ancient myths and deep psychological fears. Max Ernst used art not to depict beauty but to disturb, awaken, and question. With brushes, collage techniques, and invented processes like frottage and grattage, he created worlds that could not be explained but only experienced. His paintings appear as cryptic dreams where rationality dissolves and the unconscious mind takes full control. In every canvas, Max Ernst whispered questions about reality, control, and the symbols buried deep within human history. His legacy remains as one of art’s greatest disruptions.

One of the core fascinations with Max Ernst lies in his obsessive use of strange creatures and esoteric symbols. In many of his works, birds, hybrid monsters, and archaic shapes appear without clear explanation. Max Ernst once imagined himself as a birdlike character named Loplop, who reappeared in multiple pieces across his career. These personal totems were more than random inventions. They carried messages from Ernst’s subconscious, layered with mysticism, myth, and a rejection of societal order. In pieces like The Robing of the Bride and Europe After the Rain, viewers find themselves trapped in a forest of visceral forms, uncertain whether they are seeing life, death, or something in between. The surreal worlds of Max Ernst do not offer comfort. Instead, they challenge the viewer to engage with a visual puzzle full of references to ancient civilizations, forgotten rituals, and imagined futures. In every glance, a new creature stares back.

“Read about: Abstract or Real? Gerhard Richter Blurs the Line Like Never Before!”

Unlike many artists of his time, Max Ernst refused to limit himself to traditional methods. He invented new ways of creating texture and meaning by embracing chaos in the creative process. Frottage, for instance, involved placing paper over textured surfaces and rubbing them with pencil to find unexpected forms. From this randomness, Ernst would develop fantastical images. He also pioneered grattage, a painting technique where the canvas is scraped to reveal underlying layers. By allowing chance to guide his art, Max Ernst created works that felt both mechanical and organic, as if grown in a dark laboratory of the subconscious. His artistic process rejected control and welcomed accident. What emerged were visions that could not have been planned, only discovered. These textures gave his paintings a physical unease, as if the viewer were touching the skin of a creature not meant to exist. The madness was not decoration. It was method.

The strange genius of Max Ernst reshaped not only visual art but the understanding of how creativity and psychology intertwine. Inspired by the writings of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, Ernst explored the unconscious with a brush instead of words. His works acted like inkblots in a Rorschach test, drawing out meaning from the viewer rather than explaining anything directly. Artists like Salvador Dalí and Jackson Pollock would later echo this approach, but it was Max Ernst who first dared to show the mind’s ugliest dreams and divine mysteries on canvas. His influence stretched beyond painting into sculpture, collage, and even film. The art world was permanently changed. Not by rules or perspective, but by the invitation to lose control and follow the irrational. Today, museums display his work not only as historical pieces, but as maps to mental landscapes we still struggle to name.

“Read more: Gen Z Can’t Get Enough: The Martha Stewart Aesthetic Is Taking Over Homes in 2025!”

Even now, Max Ernst remains an enigma. His work resists definition, and perhaps that is the point. Every piece invites interpretation but denies conclusion. He did not paint to be understood. He painted to provoke and confuse. Through birds with human faces, castles floating in smoke, and skies bleeding from invisible wounds, he told stories that feel half-remembered from a dream. Critics have tried to pin him down as madman, genius, prophet, or trickster, but none of these words fit completely. The truth is, Max Ernst exists in the in-between. His art is the mirror of our forgotten fears and desires, placed in a gallery where reason is banned. To see his work is to accept the discomfort of not knowing. And in that mystery lies his power. He did not just change how we look at art. He changed how we see ourselves through it.